Your cart is currently empty!

Critical Theory: A Psychosis

What is Critical Theory?

Critical Theory, first introduced in the 1930s by the Frankfurt School—a group of German philosophers and social theorists including Max Horkheimer, Theodor Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, and Walter Benjamin—aims to address issues of social inequality, power, and domination. Drawing on Marxism, psychoanalysis, and existentialism, these scholars sought to critique and change society by examining the underlying power structures and cultural dynamics that perpetuate social injustices. Since its inception, Critical Theory has gained broader recognition and influence, particularly in the United States, in the post-World War II era as members of the Frankfurt School emigrated due to the rise of Nazism in Germany.

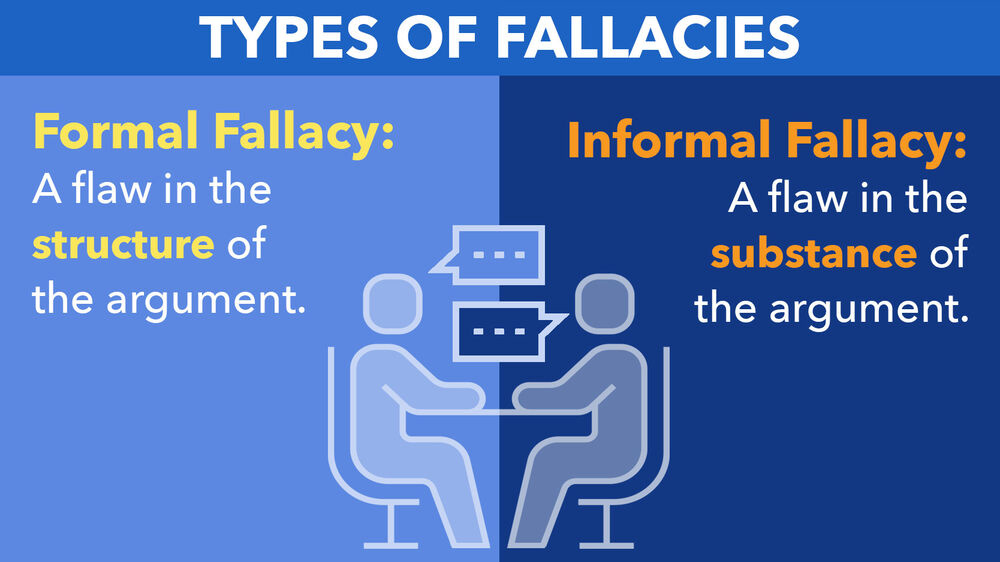

In recent years, Critical Theory has become a dominant force in college classrooms across the United States. Promoted as a tool for understanding and addressing systemic inequalities, it purports to unveil hidden power dynamics and foster social justice. However, a closer examination reveals that Critical Theory is rife with logical fallacies, leading to a kind of intellectual psychosis among students. This psychosis oversimplifies complex social realities into binary oppositions, warping the minds of young adults and eroding critical thinking skills.

Appeal to Authority: Blind Faith in Academic Credentials

One of the most prevalent logical fallacies in Critical Theory is the Appeal to Authority. Students are often taught to accept the assertions of Critical Theory scholars without question, merely because of their academic credentials. For example, students might be expected to accept Judith Butler’s complex theories on gender performativity simply because Butler is a prominent figure in gender studies, rather than critically engaging with the evidence and reasoning behind her arguments. This stifles independent thought and critical examination, encouraging a blind faith in the infallibility of those in positions of academic power. Instead of fostering a healthy skepticism, students are trained to parrot the perspectives of their professors, mistaking academic titles for ultimate truth.

Hasty Generalization: Broad Claims from Limited Evidence

Critical Theory frequently relies on Hasty Generalizations, making sweeping claims about society based on selective or anecdotal evidence. For instance, it asserts the pervasive existence of systemic oppression based on isolated incidents, without providing comprehensive data to support such broad conclusions. A concrete example is the claim that the entire criminal justice system is inherently racist based on individual cases of police brutality, without considering comprehensive statistical data that might provide a more nuanced view. This leads students to adopt an alarmist and often inaccurate view of social structures, seeing oppression where it may not exist and missing nuances that are crucial for a balanced understanding.

Ad Hominem: Attacking the Critic, Not the Argument

In the realm of Critical Theory, dissenting voices are often met with Ad Hominem attacks. Critics are labeled as racists, bigots, or ignorant, rather than their arguments being addressed on their merits. For example, when conservative scholar Heather Mac Donald critiques the concept of systemic racism, she is often personally attacked and labeled as a bigot, rather than her data-driven arguments being engaged with seriously. This tactic not only silences legitimate debate but also creates an environment where students fear speaking out against prevailing dogma, lest they be personally attacked or ostracized.

Begging the Question: Circular Reasoning

Another logical flaw in Critical Theory is Begging the Question, where the existence of systemic oppression is assumed as a given and used as a foundational premise for further arguments. This circular reasoning means that the theory is never truly tested or questioned; it simply reaffirms its own assumptions. For example, in discussions about gender inequality, the assumption that all gender disparities are a result of systemic sexism is taken as a given, and all further arguments are built on this premise without critically examining other potential factors. Students are thus caught in a feedback loop, constantly reinforcing the belief in systemic oppression without ever critically examining its validity.

False Dilemma: Oversimplified Binaries

False Dilemma is a hallmark of Critical Theory, which often presents social issues in terms of binary oppositions: oppressors versus oppressed. This oversimplification ignores the complexities and nuances of real-world power dynamics. For example, in discussions about economic inequality, the narrative is often reduced to the wealthy oppressing the poor, without considering the roles of innovation, market dynamics, and individual choices. Students are taught to see the world in black and white, missing the shades of gray that are essential for a nuanced understanding of society. This binary thinking can lead to increased polarization and an inability to engage in constructive dialogue with those who hold different views.

Straw Man: Misrepresenting Opposing Views

Critical Theory frequently employs Straw Man arguments, misrepresenting opposing viewpoints to make them easier to attack. For example, critiques of Critical Theory are often caricatured as ignorant or malicious, rather than being engaged with seriously. When someone argues that meritocracy is an ideal worth striving for, they might be misrepresented as denying any existence of privilege or structural barriers. This not only disrespects legitimate intellectual debate but also deprives students of the opportunity to refine their own arguments through rigorous challenge.

Equivocation: Ambiguous Language

The use of Equivocation in Critical Theory, where terms are redefined to suit the argument, further muddies the waters. Words like “racism” are redefined to encompass systemic and institutional power dynamics rather than individual prejudices. For instance, the redefinition of “violence” to include speech acts creates confusion and obscures the real issues at hand, making it difficult to engage in clear and productive discussions. This shifting of definitions can confuse students and obscure the real issues at hand, making it difficult to engage in clear and productive discussions.

Slippery Slope: Alarmist Predictions

Slippery Slope arguments are another tool in the Critical Theory arsenal, suggesting that any challenge to its tenets will lead to extreme negative outcomes, such as a total regression to a more oppressive society. For example, arguing that questioning affirmative action policies will inevitably lead to the reinstatement of segregation laws is a Slippery Slope fallacy. These alarmist predictions create a climate of fear, where students feel that even questioning the theory could have dire consequences. This stifles open debate and reinforces dogmatic adherence to the theory.

Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc: False Causation

Critical Theory often falls into the trap of Post Hoc Ergo Propter Hoc, assuming causation from correlation. It posits that because certain social disparities exist, they must be directly caused by systemic oppression. For example, the higher incarceration rates of certain minority groups are often attributed solely to systemic racism, without considering other factors such as crime rates, socioeconomic conditions, and personal choices. This simplistic reasoning ignores other potential factors and leads students to draw erroneous conclusions about the nature of social problems.

Appeal to Emotion: Manipulating Feelings

Finally, Critical Theory heavily relies on the Appeal to Emotion, using emotional appeals to persuade rather than logical arguments. By invoking feelings of guilt, anger, or empathy about social injustices, it seeks to garner support without providing solid evidence. For instance, showing graphic images of police brutality without context is meant to evoke strong emotional responses, which can cloud students’ judgment and make them more susceptible to adopting the theory uncritically.

What does this mean?

The prevalence of these logical fallacies within Critical Theory is creating a form of intellectual psychosis among higher educated demographics. By oversimplifying power dynamics and discouraging critical examination, it is warping their understanding of society and stifling genuine intellectual growth. For the sake of fostering true critical thinking and a nuanced understanding of social issues, it is imperative that we address these flaws and promote a more balanced and evidence-based approach to education.

Leave a Reply